Last updated on October 5th, 2023 at 10:55 am

Not all minerals are created equal. That’s why it’s important to know the difference.

Cutting costs in a business that can be as financially unpredictable as ranching is a given. A sharp pencil and close attention to the bottom line can make the difference between a happy banker and a hard conversation on your next visit.

But it’s important, essential even, to manage input costs carefully. Why? Because you can’t sell a dead calf.

That’s what one ranch learned, according to Dr. Jeffery Hall, professor of toxicology, veterinary diagnostics, and mineral nutrition in the Department of Animal, Veterinary and Dairy Sciences at Utah State University.

Dead calves? Maybe it's a mineral deficiency.

Speaking during a March 2021 Riomax® Rancher Round Table webinar (CLICK HERE to watch it), Dr. Hall related an experience from one ranch he works with. “We got their mineral program where it needed to be and they were really doing well,” he said. “Then this year (2021) they started bringing dead calves in again and we started seeing mineral deficiencies all over again.”

Dr. Hall called the ranch owner, who said he had turned the day-to-day work over to his boys. “And I told him what we were finding,” Dr. Hall says.

The rancher called back in about a week, “And his boys decided the mineral was too expensive,” Dr. Hall related. “So they cut back to a really low-quality mineral, what I categorize as a very poor mineral. They were putting mineral out, but basically got what they paid for.”

At the time Dr. Hall made his presentation, the ranch was losing 8% of its calves within the first two weeks of life. “And every calf we tested was mineral deficient.”

So, how do you define a 'poor cattle mineral'?

“First, I always tell people to look at the numbers,” Dr. Hall said. How much copper is there? How much selenium is there? How much zinc is there? How much manganese is there? What is the cobalt? “Look at the different minerals, but also take into account what the intake rate should be.”

That’s because, comparing intake for a 2-ounce mineral versus a 4-ounce mineral, a 2-ounce mineral should have about double the intake because they're eating half as much. “Or if you're feeding a product that has a pound per head per day, it should have about a fourth as much as a product feeding 4 ounces per head per day,” Dr. Hall said.

“So you have to look at the numbers in conjunction with recommended daily intake. But then you have to take it to the next step.”

That’s looking at and understanding the differences between chemical forms. “And the particular product they were using was a really high salt-based mineral, too high for the area. So I doubt that the cows were eating anywhere near what was listed on the label as far as recommended intake,” he said.

And what the cows were consuming wasn’t doing them much good. “Almost all the minerals were in the oxide form, which is one of the poorest bioavailable forms of mineral that you can feed,” Dr. Hall said. But it's also the cheapest.

What's actually in your cattle mineral?

“So basically on the tag, the numbers look great, but the chemical form was such that the cows couldn’t functionally utilize it.”

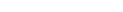

Beyond that, the area where they were feeding the mineral has a lot of sulfur-based interferences. Sulfur can cause major interferences with absorption of the minerals important to calf well-being—selenium, copper, zinc, manganese.

“So not feeding some form of organic or true rumen-protected bypass mineral, there's no way the cows were going to be able to absorb enough.”