Last updated on October 2nd, 2023 at 11:06 am

“I’ve never known a man to go broke being understocked. Now, you may leave a little money on the table, but you’re not going to go broke.”

That pearl of wisdom from his first range management professor is one of many that Dr. Tim Steffens has collected and often passes along to students, ranchers and anyone else who will take heed.

Why? “In a drought, that’s the thing you’ve got to be really scared of,” Steffens declares. He serves as an associate professor of rangeland resource management at West Texas A&M University in Canyon, Texas, and as a Texas AgriLife Extension Service range management specialist.

However, if you have a grazing and drought plan, and a good ranch inventory, you can weather what the dry years throw at you and still stay on the land, says Dr. Hector Menendez, assistant professor and South Dakota State University Extension range management specialist.

Manage so you can measure

Menendez invokes the old saw that you can’t manage what you don’t measure. “And so it’s really critical in terms of grazing management to have a ranch inventory. And by that, I mean number of cows, assets, available grass (and other forage), number of pastures, and days available for grazing,” he says. “Then that’s the first place to stop and either look at that information or quickly acquire what (information) can be acquired so that we can make objective decisions.”

Of course, not every rancher is dealing with drought. If that’s your situation it’s still important to have a current ranch inventory and drought management plan. And now’s the time to do that if you haven’t already got those in place.

➔RELATED: Download a ranch inventory sheet & drought plan.

In times of drought, having those at your fingertips is critical. If there’s adequate forage for cows and calves, you can supplement to extend the grazing season, Menendez says. By determining the number of days left to graze any particular pasture, you can pull the cattle before harming the resource.

There are several often-used ways to do that:

- You can cull cows to reduce stocking rate and supplement to extend the forage

- You can find additional pastures with adequate forage and move the pairs

- You can wean early

- You can drylot the cattle

Setting drought trigger dates

Once you’ve determined the amount of available forage and number of grazing days left in a pasture, then you look at your drought plan for the pre-determined trigger dates. Those are set by the rainfall you’ve been blessed with and available soil moisture.

These trigger dates tell you critical points in the year when decisions need to be made, Steffens says. Those decisions depend on how much forage you have at that time and when you can reasonably expect growth again.

“So at that time, you need to get forage demand in line with forage supply—you can carry a lot of cattle for a very short time or a few cattle for a long time with the same forage supply,” Steffens says. “Think of like a barn full of hay.”

Measuring Rainfall

The rainfall, of course, determines the amount of forage growth. Thus, drought is determined not only by the amount of precipitation you do or don’t get, but when you get it, how much soaks in versus how much runs off, and how much evaporates. “If you look at the entire Great Plains, basically, your most reliable rainfall, and the rainfall that’s coming during times when the temperatures are right to grow grass efficiently, is April, May, June by and large,” Steffens says.

“If you don’t get the growth then, even if you get rainfall after that, that rainfall isn’t going to grow as much grass as the rainfall would have before.”

Menendez agrees. “Once you hit those April-May dates where you need to have that rain to get those rangeland forages in production, the likelihood of having additional forage is really low. The statistical probability, over a 40-year weather average, is really low for them to have the time that plants can grow and recover.”

That’s because, once you get into summertime, plants begin to mature and set seed, Steffens says, and evaporative losses increase because of hotter weather. “When they start setting a seed head, they’re done making leaf. And so, you may get some green-up (if you get rain late in the growing season), you may even grow it up a little bit, but it’s going to set a seed head and it’s done.”

Keeping Cover Crops

Indeed, while late summer and fall rain is a blessing, it can quickly turn into curse if you succumb to green-up fever. “Although those cool season grasses may bounce back, really, you’re going to probably harm them more than the benefit you get from additional grazing,” Menendez says.

That’s because the plants need to store energy for the following growing season. “If you’re knocking them down to a point where their energy reserves and those roots are really being damaged, you’re setting yourself up for a worse situation the subsequent spring,” he emphasizes.

Beyond that, keeping some cover on the ground helps the precipitation soak in instead of running off, Steffens says, which helps set the plants up for success the next year. That’s especially important if you’re feeding cows on pasture.

“They’re not just going to eat the hay. They’re going to go out and nibble around on whatever starts to grow,” Steffens says. “Well, if that grass just starts to get its head up and something comes along and bites it off, it sets it back even worse. You end up destroying the resource, losing your equity, and you’re not making any money, either. So keeping those things in mind keeps you from getting into wrecks.”

Managing Ranch Equity Equally Important

Menendez and Steffens agree that managing your equity is just as important as managing your grazing, especially in a drought. That means work the spreadsheets hard, they say. That’s because of another old saw that maintains that you can’t feed your way out of a drought.

“When you start getting into a drought, you need to worry about managing water and the plants, and you do that with cover,” Steffens says. “You’ve got to manage equity, and you do that by not spending a bunch of extra money. Then, you manage how well the livestock do by getting your carrying capacity in line with the other two.”

Steffens says, if you look at the cost of hay and diesel, you can’t afford to haul hay to your cattle. “You’re better off to haul the cattle to somewhere that has grass or get your money back out of them. Take the cash, have the equity, and preserve the resource.”

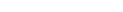

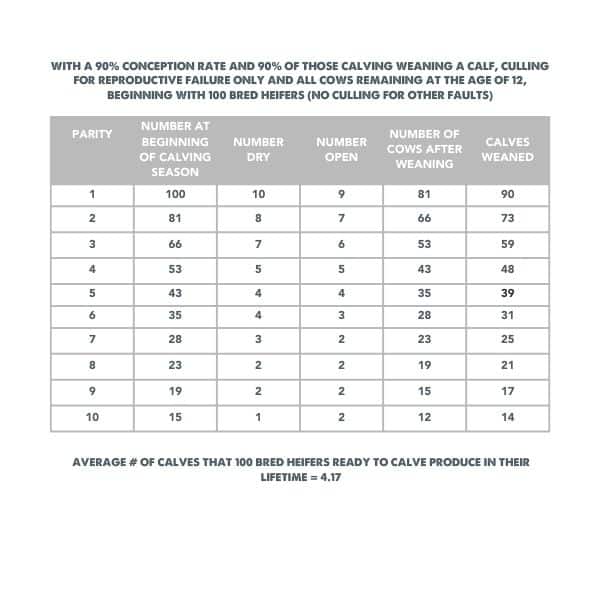

Looking at things objectively, Steffens says the average cow will produce five calves in her lifetime. (See Tables 1 &2.) If you keep one of those calves as a replacement heifer, then you’re down to four calves you can market. “And then, if you look at what she’s going to bring as a cull cow, compared with what she is worth coming into the herd as a bred heifer, you’ve got a lot of depreciation to make up with those four,” he says.

Ranch Inventory

That doesn’t mean you shouldn’t spend some money. But it does mean it’s important to spend wisely.

Enter the ranch inventory. You need to consider both your fixed costs and your variable costs and the ranch inventory will tell you that, Menendez says.

As you’re considering all your options, be objective, Menendez says. “Making those objective, hard decisions based on numbers and measurements is really critical, having been there myself with a cattle herd in Texas and having to make those decisions,” he says. “But by being really objective about it, it will set the rancher up for long-term success.”